Current projects:

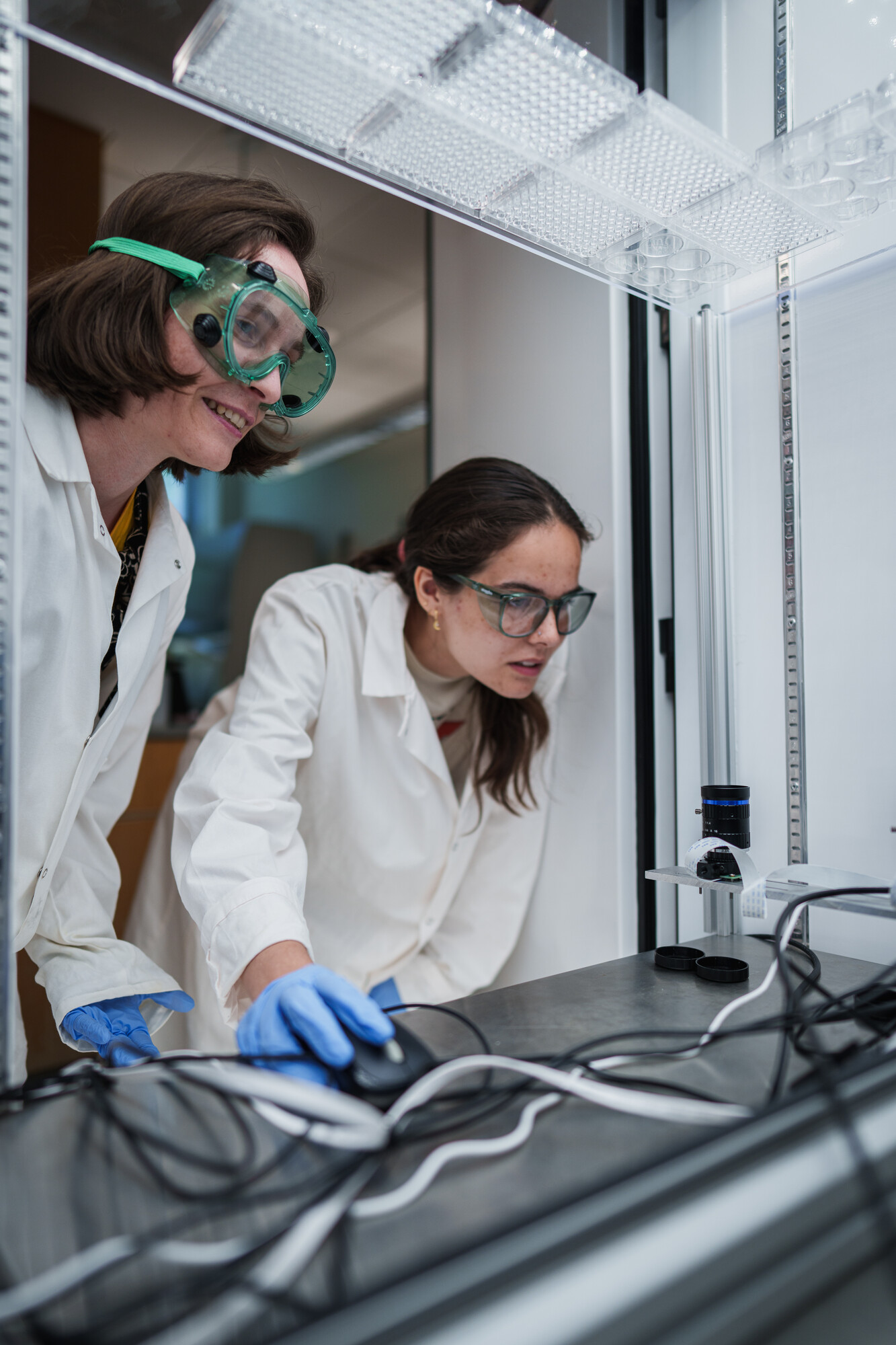

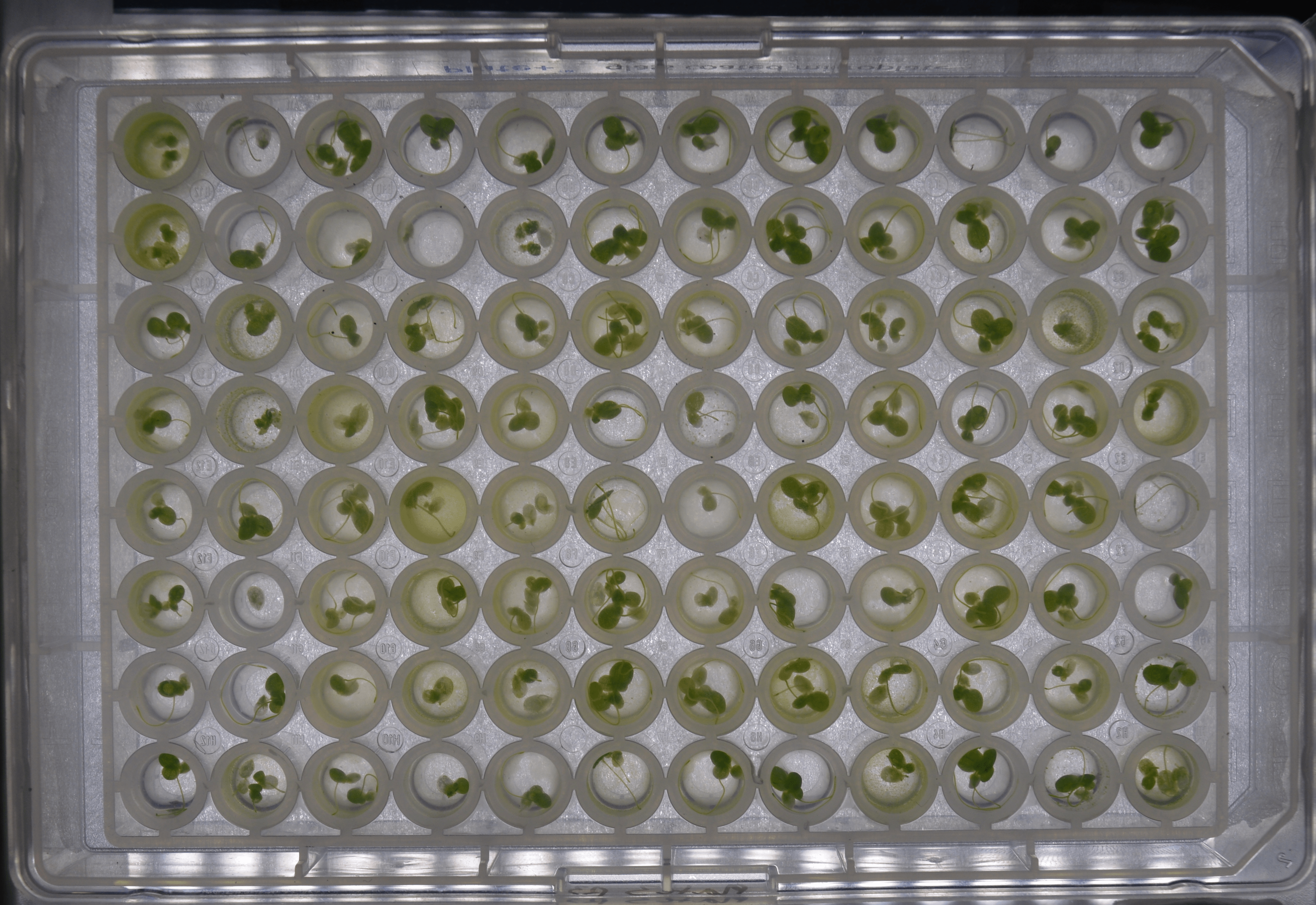

Experimental evolution of plant-associated microbiomes We aim to develop and test theoretical predictions on microbiome selection practices - which are the most effective? repeatable?. We select on duckweed growth rates in different conditions, or with different, synthetically combined, starting microbiomes (Emma Kinerson, Ciana Lazu). So far, we have found that starting microbiomes including microbes from very closely related (another duckweed) or very distantly related (a floating liverwort) improve responses to microbiome “breeding” in duckweeds.

Duckweed green manures We have found (like others) that duckweed applied as a soil amendment can improve the growth of plants, and that duckweeds paired with microbes from farm ponds are very effective at removing phosphorus from pond water. This suggests that duckweeds could be great at recapturing runoff nutrients, reducing fertilizer loss and nutrient pollution. However, we have also found that cyanobacteria associated with duckweeds may transfer toxins into green manure materials, which is a safety concern. (Alyssa Daigle, Matthew Farbaniec).

The seasonal dynamics of host-associated microbiomes Working with local duckweeds, we have so far found that microbes isolated from the summer improve duckweed growth the most, and that there is a weak signal of local adaptation between duckweeds and microbes only in the context of their local water (Alex Trott, Ava Rose, Emma Kinerson, and Ethan Morgan). We are in the midst of some sequencing work!

Effects of hosts on microbiome recovery Soil steaming kills both weed seeds and microbes, and offers a model to understand the effects of hosts on microbiome (re)assembly

Past projects

The novel stressors of global change and plant-microbe interactions

Urbanization of landscapes brings previously un-encountered stressors, from urban heat islands to chemical-laden surface runoff, and such novelty may perturb plant-microbe interactions. Runoff contaminants disproportionately affect freshwater species, such as duckweed and its microbiome. Duckweed is tiny (fronds 2-5 mm) and reproduces rapidly (clonal generations in 3 days), making it highly amenable to experimentation. Duckweeds host a mutualistic and diverse microbiome, of which many species can be lab-cultured (O’Brien et al, 2020), facilitating microbiome manipulation. Together with chemical engineers, I found that contaminant stressors (metals, salt, and anti-corrosives), and the origin of the duckweed and its microbiome can interactively alter plant traits and benefits. In fact, microbes favor biotransformation of contaminants to less stressful or growth-promoting compounds (O’Brien et al, 2019), and urban duckweed-microbe pairs better tolerate chemical inputs (work ongoing). However, we also found that a globally ubiquitous microplastic (tire wear particles) can disrupt benefits from, and fitness correlation in, duckweed-microbe mutualisms (O’Brien et al, 2022).

Joint influences of biotic and abiotic context on evolutionary responses

With the explosion of research in microbiome science, we have become aware that microbes alter the expression of host traits (e.g. plant phenology, O’Brien et al, 2021) – but what does this mean for the evolution of such traits? With co-authors, we leveraged theoretical simulations to show that microbes can evolve substantial contributions to, and genetic variation for, host traits as a result of impacts of host fitness on their own fitness, or because traits separately influence their fitness. We further demonstrated that while evolution reaches new optima more rapidly when hosts and microbes have fully aligned fitness optima, differing optima can maintain more genetic variance (O’Brien et al, 2021). In duckweeds, differences in phenotypes among hosts are consistent when hosts are grown in similar microbiomes, but host genotypes provide little information about phenotypes when moving hosts to a very different microbiome (see preprint).

By shifting in outcome across gradients, and by influencing expressed phenotypic variation on which selection can act, biotic interactions might drive phenotypic divergence across environments. My co-authors and I tested the role of species interactions in phenotypic divergence across climate in teosinte (Zea mays ssp. mexicana, a wild annual grass closely related to maize). Using populations of teosinte and associated rhizosphere biota (microorganisms living in, on, or near roots) sourced from along a climatic gradient, we found that biota alter expression of most measured teosinte traits (see O’Brien et al, 2019, featured in the Digests). We additionally discovered that a number of biota-altered traits of teosinte both underlie adaptive divergence across climate, and contain rhizosphere-dependent genetic variance and covariance: later flowering and larger roots may be selected at warmer, drier sites, and genetic covariance of these traits shifts across biota for some teosinte populations. Consequently, we expect some biota would facilitate, and others restrict, responses to present day selection pressures.

Species interactions are often conditional, meaning fitness outcomes vary across circumstances. Despite decades of research commonly identifying that stressful (cold, infertile) conditions shift interaction outcomes more mutually positive, or at least less antagonistic, the evolutionary implications remain largely overlooked. My co-authors and I predicted the evolutionary consequences of interaction outcomes structured by abiotic gradients using theory and simulations (O’Brien et al, 2018). We posited that as interactions shift towards more positive fitness outcomes for both partners in stressful environments, selection will favor mutualistic adaptation and co-adaptation: genetic variants in a focal species that increase fitness of a partner will indirectly positively affect their own fitness, and thus increase in frequency. We then used teosinte and its associated rhizosphere biota as an experimental test: asking whether mutualistic local adaptation between teosinte and rhizosphere biota is stronger in stressful sites. We indeed found increased local adaptation between plants and biota from stressful sites, but biota from stressful sites were not broadly mutualistic (O’Brien et al, 2024).